GENERAL INFORMATION

OVERVIEW

Most of us are aware of our heart and know that it pumps blood around our bodies, keeping us alive. The continuous and smooth flow of blood around our body is essential; formation of a blood clot in the wrong place—known medically as thrombosis—can cause interruption of normal blood flow and result in illness, which in some cases can be life threatening [1].

A blood clot within the veins or arteries, which are the vessels that form our ‘cardiovascular system’, causes a number of common and well-known cardiovascular illnesses. Blood clots forming in veins can cause deep vein thrombosis (called DVT for short) [1]. A ‘pulmonary embolism’ (PE for short) results from a blood clot in the arterial blood supply to the lungs [1]. Blood clots in arteries supplying blood to the heart can cause a heart attack [2] and clots in arteries supplying blood to the brain can cause a stroke [3].

In this section, we will explore the biology of blood clotting and examine how our bodies form blood clots and why thrombosis occurs.

NORMAL BLOOD CLOTTING

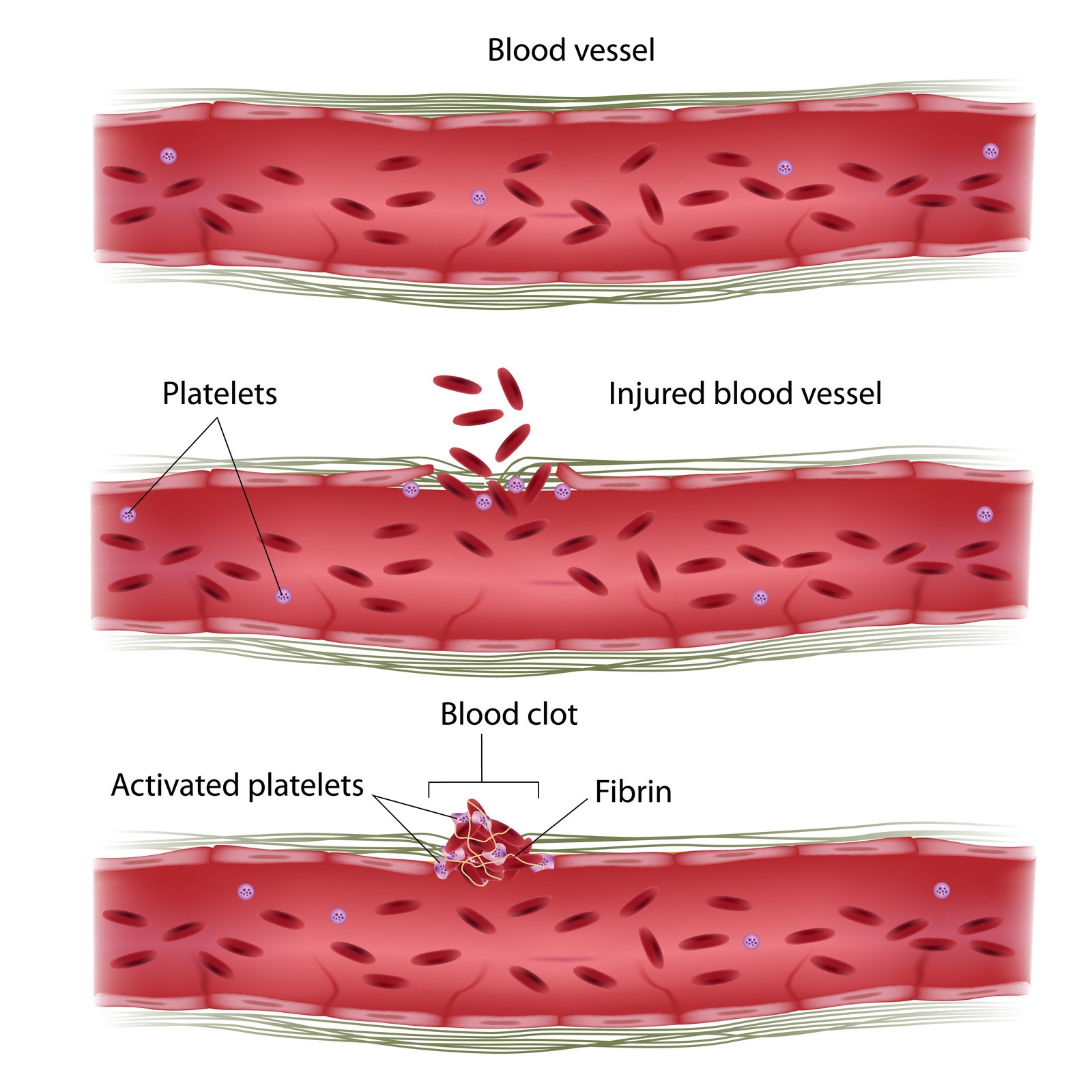

We all know that if we cut our skin, a clot forms that stops blood loss from the injury. This process is known as ‘haemostasis’ and is the body’s normal response to injury. The first step in the process of haemostasis is the narrowing of an injured blood vessel, which constricts and limits blood flow in the vessel. Clotting then begins, in which blood changes from a liquid to a gel. Blood particles called platelets clump and stick to the vessel wall and they interact with and activate other proteins to form fibrous strands called fibrin [4]. These strands form a net that catch other blood cells and help to produce a clot.

The image shows platelets and fibrin combining to form a clot and seal a wound.

The formation of a clot is balanced by another process that stops clotting and breaks down and removes a clot once the vessel has repaired. The process of haemostasis exists in balance to ensure excessive bleeding or excessive clotting does not occur. An imbalance in the blood clotting system can lead to excessive bleeding (haemorrhage) or excessive clotting (thrombosis) [5].

THROMBOSIS

Thrombosis is the formation of a blood clot or ‘thrombus’ inside a blood vessel that significantly reduces or stops the flow of blood to or from the heart [1].

There are three broad categories of factors that disturb the normal clotting process and contribute to thrombosis [6]. These are:

- Blood flow—alterations to normal blood flow; low blood flow in veins occurs in legs after bed rest and after an operation when people are immobile [6]

- The state of the blood vessel walls—injury to the lining of blood vessels, for example caused by surgery, or changes in the vessel wall that can be caused by some metabolic illnesses such as diabetes [6]

- Blood composition—blood may clot more easily than usual, caused by changes to the contents of the blood; for example, some people with cancer experience changes in the level and activity of proteins that are part of the clotting process [6]

Doctors often refer to these categories as ‘Virchow’s triad’ after the doctor who first described them more than 100 years ago [6]. These principles are still used today by physicians diagnosing and treating patients with thrombosis.

The image shows an older lady bed-bound because of an acute medical illness; these factors—advanced age, acute illness, and immobility—can disturb the normal clotting process and contribute to an increased risk of thrombosis.

VENOUS THROMBOSIS

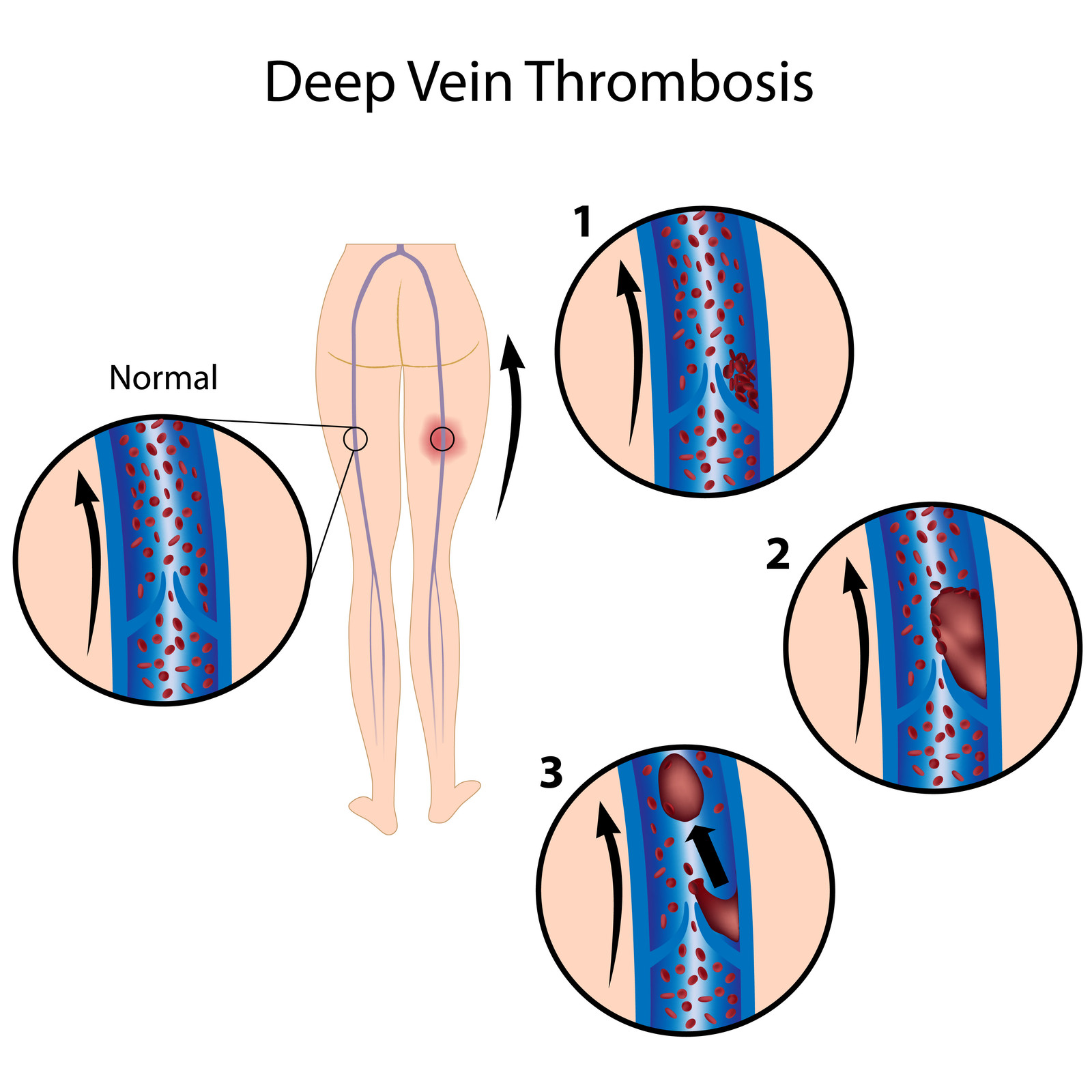

Venous thrombosis is a blood clot that develops in a vein [8]. Veins are the blood vessels that carry blood from tissues back to the heart. Blood in veins is not under high pressure as it is in arteries, and, therefore, veins have valves and require muscular movement to move blood through them and to push blood upward from the feet against gravity [9].

Because of the way blood flows through a vein, the area at the base of the valve has reduced blood flow. If the body's normal blood clotting system is out of balance, platelets can begin to attach to the blood vessel wall, triggering fibrin formation, and a clot begins to form [6].

Figure: step 1 shows a small clot forming at the base of a valve. Step 2 shows the clot growing in size and step 3 shows a part of the clot breaking off. This detached clot—called an ‘embolus’—can then travel further up the body. The formation of a thrombus that becomes embolic is called ‘thromboembolism’.

A form of venous thrombosis is a DVT, which is when a clot forms in the deep veins of the leg [1]. If an embolus breaks off and moves up the leg, through the heart, and lodges in a lung artery, a person suffers a PE [1]. These related blood clot problems— DVT and PE—are known as ‘venous thromboembolism’ (VTE for short) [1].

VTE matters because it is a common cause of death in Australia [10]. Learn more about VTE on the next pages.

VTEMatters offers general information only. Please see a healthcare professional for medical advice.

REFERENCES

1. National Blood Clot Alliance. At-a-glance: blood clots. Accessed on 22 November 2018.

2. National Heart Foundation of Australia. Heart conditions. Heart attack. Accessed on 18 April 2019.

3. Stroke Foundation. About stroke. Accessed on 22 November 2018.

4. Periayah MH, et al. Mechanism Action of Platelets and Crucial Blood Coagulation Pathways in Hemostasis. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2017; 11(4): 319-27.

5. Palta S et al. Overview of the coagulation system. Indian J Anaesth. 2014; 58(5): 515–523.

6. Reitsma PH et al. Mechanistic view of risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012; 32: 563-8.

7. Rajendran P et al. The vascular endothelium and human diseases. Int J Biol Sci 2013; 9:1057–69.

8. Healthdirect. Thrombosis. Accessed on 18 February 2019.

9. The Australasian College of Dermatologists. Leg veins. Accessed on 18 February 2019.

10. The Australia and New Zealand Working Party on the Management and Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism. Prevention of venous thromboembolism (5th Edition). 2010.